Learn how to grow and style a Victorian mustache using modern tools, historical insight, and the forgotten truths behind upper-lip grandeur. You’ll see it’s not all down to genetics.

Learn how to grow and style a Victorian mustache using modern tools, historical insight, and the forgotten truths behind upper-lip grandeur. You’ll see it’s not all down to genetics.

Whether it’s a laborer with his formidable walrus or a gentleman of means sporting an expansive handlebar, you’re bound to ask how they did it. We see them in sepia portraits from the Victorian and Edwardian eras but rarely in real life.

One reason is because it’s no longer fashionable. But would we even have the potential?

Mustaches returned in the 70s and 80s, but those chevrons seldom reached the Stalin-esque proportions of days gone by—not even Tom Selleck’s fully grown-out specimen.

So, what changed?

Were men manlier?

The Perceived Importance of Mustaches

For all social classes, a boy was considered a man only when he could grow and maintain a mustache. It was a rite of passage.

This was a result of the Crimean War, when soldiers returned with rugged facial hair that became synonymous with heroism and maturity. A badge of virility worn not on the chest, but the upper lip.

The symbolic power of the Victorian mustache only deepened as the decades marched on.

By the Edwardian era, the wealthy upper lip had taken on ever grander proportions, artfully curled and held in place with wax.

For the working-class man, this level of preening would have been impractical. But he didn’t need it.

The Soldier vs. the Officer

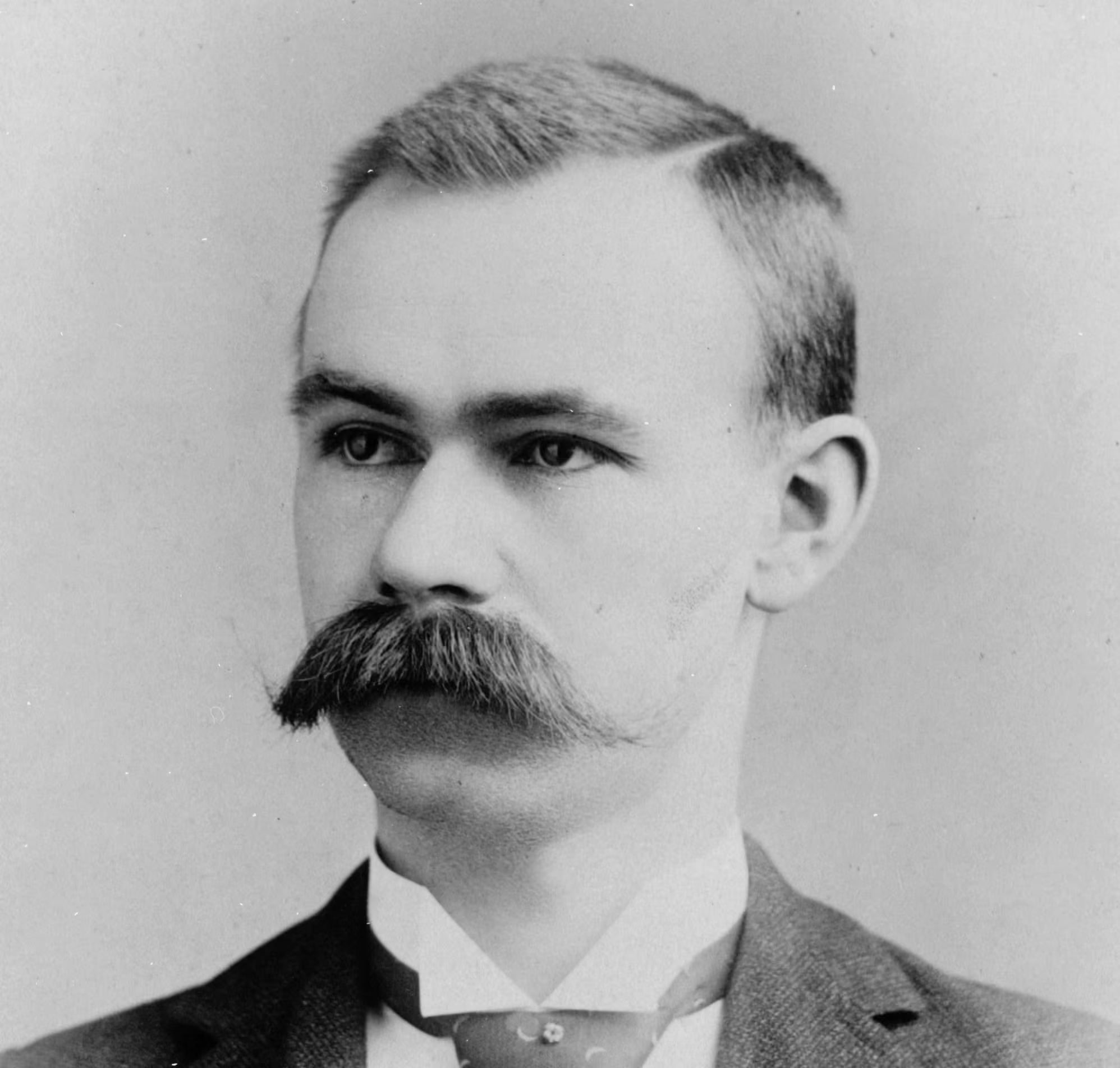

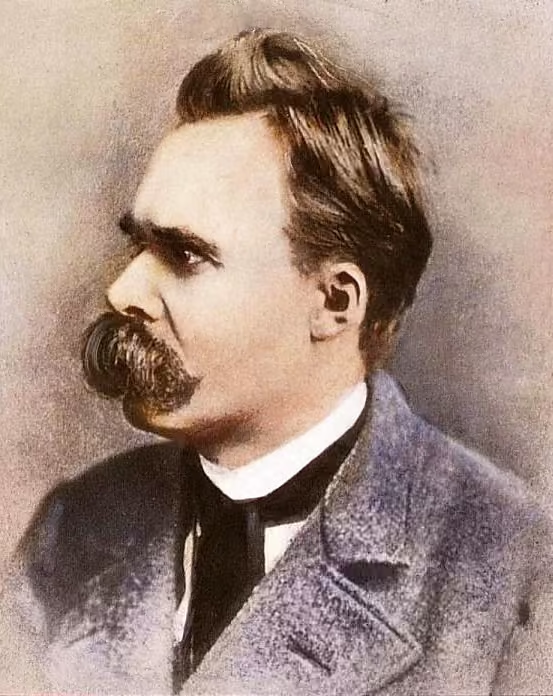

We’ve all seen pictures of Nietzsche. Admittedly, his was unusually large, but this was the type of mustache scholars, soldiers, and laborers favored. No wax, no fakery; just testosterone.

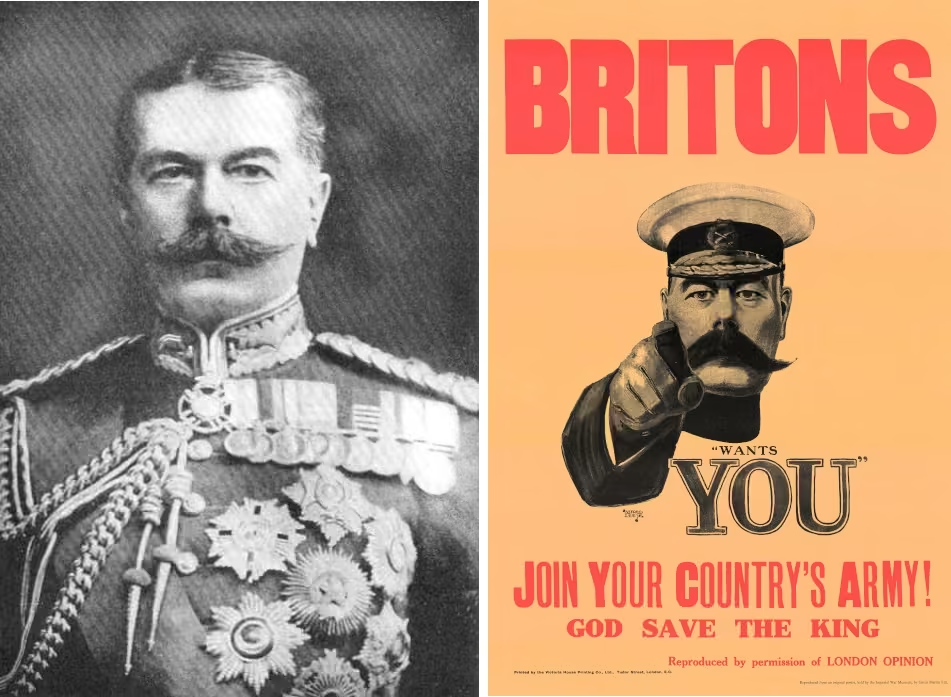

And we all know the famous poster of Lord Kitchener. Preferred by aristocrats, dandies, and ranking officers, it was the style that launched a million men.

But it may not have been entirely natural. Edwardian gentlemen relied not only on mustache wax. Switches and mascaro were also essential for achieving the desired size and volume.

We can’t be certain of whether Kitchener used these tricks, but compared to the photo from which the poster was adapted, it’s without a doubt that the artist altered the ratios.

By slimming down Kitchener’s face, he allowed the handlebar to take center stage, making it a provocative symbol of authority and manhood.

As a result, millions enlisted, and the image became one of the most enduring icons of the First World War.

What Made the Difference?

But were Edwardian embellishments merely stylish—or were they compensating for something?

The Laborer’s Mustache

Before the gym, there was the shovel and sledgehammer. Before protein shakes, there was bread, lard, and offal.

Men who engage in physically demanding jobs—like lifting, hauling, and chopping—often have higher testosterone levels and sperm counts than their desk-bound counterparts, according to a Harvard study.

As for supplements; the bygone laborer didn’t need them. He had steak and kidneys. This BBC feature shows that with every bite, he was unknowingly feeding the very hormones that made his mustache magnificent.

Meals were rich in local potatoes, whole grains, vegetables, fish, and milk—all seasonal, unprocessed, and deeply nourishing.

And when livestock was slaughtered, every part of it was consumed. Waste was an insult to the animal.

The mustache that rose from his diet wasn’t ornamental. It was earned.

The Gentleman’s Mustache

During the Edwardian era, wealthy households relied more and more on branded and pre-prepared foods. And their mustaches more and more on enhancement through artifice.

Low-fat, high-sugar, ultra-processed food may fill the plate—but it doesn’t feed the follicle. Instead, it suppresses testosterone and increases estrogenic effect.

So, in many cases, embellishments were about styling the mustache into existence in defiance of a diet that no longer supported its growth.

Still wondering why we don’t grow them like that anymore?

Mustaches of Today

But we do, I hear you say. Look at Daniel Day-Lewis in “There Will Be Blood” or Tom Hardy in “Bronson.”

Like the mustaches of bygone officers and gentlemen, these too are not entirely genuine. The real Charles Bronson (Charles Arthur Salvador) reportedly shaved off his own and mailed it to Hardy for use in the film’s prosthetics.

But Bronson is the exception.

Name him as a modern man whose mustache lives up to Victorian standards, and I’d agree without hesitation. In fact, his entire bearing belongs to another age.

He may be infamous for his time behind bars, but his physicality evokes something older and more elemental: the laborer of the Victorian age. Broad-chested and thick-armed, he resembles the kind of man whose strength came not from supplements, but from soot and strain.

There aren’t many like that nowadays.

How Your Mustache Can Look Like Theirs

For the purposes of this article, I’ve examined hundreds of cabinet cards from the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Facial hair was nearly universal, and its presence deliberately pronounced. While not every mustache was extravagant, many were fuller and more imposing than any I’ve encountered beyond page or screen.

And that’s the kind of look many mustachioed men of today aspire to—including me.

I’ve been quite lucky. Although I wouldn’t compare myself to the men of cabinet cards, my upper lip more than holds its own in the current age of patchy whiskers. So much so that I’m often asked how I do it. This is why I’ve dedicated an entire article to healthy growth—you’ll find it here. It covers everything from brushes and combs to oils.

This post, on the other hand, is about achieving volume when all else fails.

Plan of Campaign

So, let’s talk tactics.

Whatever you do, start with the laborer’s method above: through diet and increased physical exertion. Follow the links and make sure you’re giving your stache all it needs to thrive.

And until it’s fully flourished, you can apply one or some of the many mustache secrets employed by Victorian and Edwardian gentlemen.

Secret No. 1: Wax

Victorian Version: Wax was essential for shaping and holding elaborate styles like the handlebar or imperial. Made from beeswax and lanolin, it was softened with the fingers before application. If the ends were curled with irons, the wax doubled as protection against heat damage.

Modern Counterpart: Today’s waxes are more refined, and there are many to choose from, either soft or stiff setting.

Boldness begins with definition, which you’ll achieve with a product like Brother’s Love Clear Gel. Offering a strong hold without residue, it’s perfect for sculpting a perfect curl.

For men with light-colored whiskers, try Brother’s Love with a hazelnut tint—darkening creates an illusion of density.

Secret No. 2: Mascaro

Victorian Version: Mascaro was a tinted pomade used to darken and define the mustache, as well as cover grays. It gave sparse whiskers a fuller look and helped maintain a uniform color—especially useful for portraits and public appearances.

Developed by Eugene Rimmel, this product eventually became mascara, used to enhance women’s lashes. For the full story, go to James Bennet’s Cosmetics and Skin.

Modern Counterpart: Tinted brow gels like Thick It. Stick It! by NYX do the same job, but with more finesse. They add subtle density and color without smudging or transferring, and are easily applied with a spoolie brush.

Choose cool ash brown for natural-looking results.

A few years ago I found a mascara by H&M Man, but such products can’t simply be painted on without appearing artificial—mostly because they’re far more viscous than brow gels. Dab gently along the upper contour of the mustache, then blend downward with a boar bristle brush for a natural-looking finish.

Secret No. 3: Darkening Shampoos and Rinses

Victorian Version: Some men used homemade rinses—like walnut hull infusions or iron-rich tonics—to darken their mustaches over time. These methods were messy, inconsistent, and prone to staining.

Modern Counterpart: Enter Just For Men Control GX, a gradual darkening shampoo that builds color subtly with each wash—ideal for men seeking a richer tone without committing to full dye.

For blending grays without full coverage, I prefer Men’s Master Repigmenting Shampoo, which darkens white whiskers to even out overall color.

Secret No. 4: Dye

Victorian Version: Dyeing was a bold move, often done with coal-tar-based formulas or metallic salts. The results could be dramatic—but also toxic, uneven, and prone to staining everything from collars to cups.

Modern Counterpart: Today’s dyes are safer and more precise. Brands like Just For Men Beard & Mustache or RefectoCil lash dye offer natural shades and easy application. I’ve dedicated a whole post to dying facial hair.

Secret No. 5: The Mustache Snood

Victorian Version: Gentlemen took bedtime seriously. To protect sculpted whiskers from crushing, they wore snoods—soft netting wraps that preserved shape and prevented pillow friction. The mustache thus remained immaculately styled even upon waking.

Modern Counterpart: Whether you’re growing it naturally or keeping a glued-on masterpiece in place (more on that in a moment), today’s snoods do the same. Now called “mustache holders,” these are still available online by Stern, or you may ask your barber when you go for your next trim.

Secret No. 6: The Switch

Victorian Version: Switches—small tufts of hair—were sewn or glued into the mustache to add volume or length. They were made from human hair or wool and applied with spirit gum.

Modern Counterpart: You could probably ask a wigmaker to fix you up with a switch, but I’ve found nothing online.

I do, however, know of a DIY trick.

To extend the ends of your mustache, attach tufts of hair from your head (or another body area) with Brother’s Love Gel. Although fiddly, it works—I know, I’ve tried it.

Secret No. 7: The Fake Mustache

Victorian Version: Aristocrats and portrait sitters often relied on false mustaches to enhance their appearance. These were crafted from human hair or wool, knotted onto lace, and applied with spirit gum.

Modern Counterpart: Today’s theatrical mustaches—like those from Kryolan, available via Alcone—are more lifelike, durable, and easy to apply. Made from real hair, they’re used in film, cosplay, and personal styling.

I’d certainly use one if I lost my mustache for any reason.

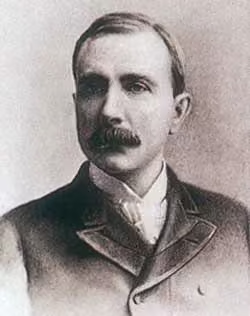

In the 1890s, for example, the titan of industry John D. Rockefeller developed alopecia during a period of intense stress and depression. By 1902, his notable walrus had vanished.

Men wearing prosthetics daily should secure with Pros-Aide, which adheres better than spirit gum. After all, what could be more embarrassing for a man than to shed his whiskers in public?

Whether your mustache is natural, styled, or glued, it remains what it was for the Victorian man: a symbol of manhood shaped by time, technique, and tenacity.

© 2025 J. Richardson

Related Posts

Disclaimer

The information provided by The Neat and Tidy Man (“we,” “us,” or “our”) on theneatandtidyman.com (the “site”) is for general informational purposes only. While we endeavor to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, adequacy, validity, or availability of any information on the site. Under no circumstance shall we have any liability to you for any loss or damage of any kind incurred as a result of the use of the site or reliance on any information provided on the site. Your use of the site and your reliance on any information on the site is solely at your own risk.